Continued from: Dublin

What follows is a fictionalized reconstruction. The facts are few, but the story they tell through informed speculation is rich, shaped by what is known about Irish emigration in this period and what meager facts are known of the Heenan family and the people that once lived, and breathed, and loved, but are now lost to time. Where the records speak, I say so. Everything else is the story I think is most likely true.

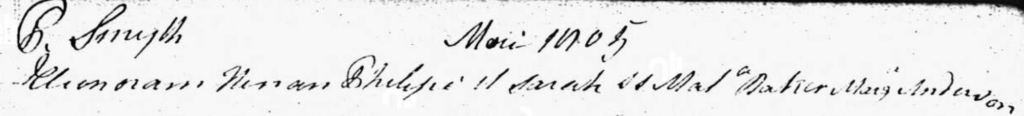

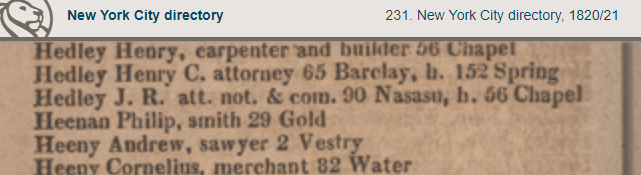

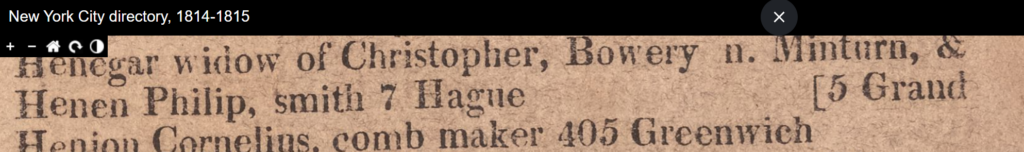

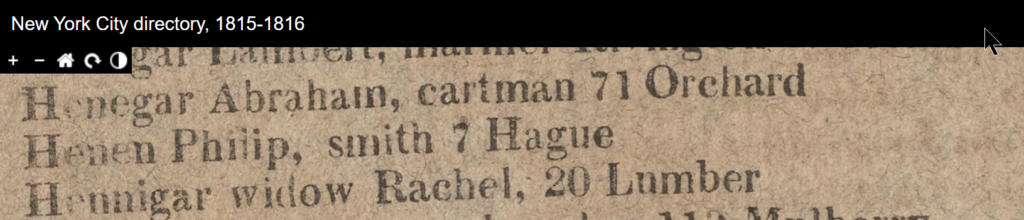

The last record of the Heenan family in Dublin is the birth of their son William, in 1809. The next sight of them is a single line in the 1814 Directory of the City of New York: Henen Philip, smith, 7 Hague. Between those two facts, a baby born in Dublin and a blacksmith established on a street in lower Manhattan, lies a crossing that no known document records. No passenger list. No ship manifest. No port of arrival notation. Nothing but silence, and the certainty that somehow, between 1809 and 1814, they made the passage to America.

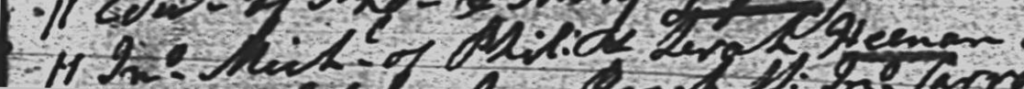

The Atlantic during the first decade of the 1800s was not yet the well-worn emigrant highway it would become later in the nineteenth century, when the wars had ended, and the traffic swelled to a flood. In those early years, the ocean was a war zone. Britain and Napoleonic France had been tearing at each other since 1803, and their conflict had swallowed the sea lanes whole. The Royal Navy controlled the North Atlantic with an iron grip, stopping and searching merchant vessels at will, and pressing into service any man they judged to be a British subject, including, according to the King, every Irishman alive. You could be a blacksmith from Dublin with a wife and children, but if a British naval officer decided he needed hands, you were in the King’s navy, and your family could wait forever.

The Americans had tried to stay out of the conflict, but failed. British actions against American ships and a series of retaliatory trade laws had strangled commercial shipping across the Atlantic, which in turn almost completely shut down passenger travel. A pair of bills passed in 1809 and 1810, intended to bolster American shipping, opened a small window for emigration until that door slammed shut with the declaration of war in June of 1812. Most likely, Philip took advantage of that window. The records don’t tell us exactly when he left Dublin, but it was surely in late 1810 when passages became slightly easier or 1811 before the war started. If he did leave in 1810 or 1811, he caught a narrow window. The worst of the American trade restrictions had eased. The War of 1812 hadn’t started yet. The Napoleonic Wars still made every crossing a risk, but the risk was manageable

Even though he was a skilled tradesman, given that they were Catholics in a city heavily oppressed by British rule, it was unlikely they had the resources for the entire family to make the journey. Shipping had increased, and there were more berths available for transport, yet it was still significantly more expensive during those years than it was prior to the wars, or after.

That historical reality, as well as the pattern of Irish emigration in this period, suggests that he most likely went alone. This was how it was usually done. The husband crossed. He found work, found a room, found his footing. And then, when he could afford the passage and had a place to put them, he sent for his wife and children. It was the practical, economical choice. What Philip and Sarah didn’t count on was America declaring war on Britain, and the withering impact that would have on all Atlantic travel, and the years of separation that came.

He would have made his way to the Dublin docks and then to Liverpool. Many Dublin emigrants took a coastal vessel or a packet across the Irish Sea to Liverpool first, then booked their Atlantic passage from there. It added days to the journey and shillings to the cost, but Liverpool was the great funnel of emigration, with more ships, more departures, more options. If Philip took this route — and the odds favor it — what he found there was chaos. The docks stretched for miles along the river Mersey, a forest of masts and rigging, the air thick with coal smoke and tar and the smell of the river. Emigrant agents worked the streets near the waterfront, booking passages on cargo vessels that carried human beings as a profitable sideline. The ships were not designed for passengers. They were merchant vessels — brigs, barques, sometimes small full-rigged ships — that had been fitted with rough wooden bunks in the lower decks to squeeze in as many paying bodies as they could alongside the cargo. Steerage. That’s what they called it, because the cheapest berths were near the stern, close to the rudder mechanism, in the darkest and most airless part of the ship.

Philip would have paid his fare — perhaps three to five pounds, a significant sum for a blacksmith but not ruinous — and been assigned a berth. A wooden shelf, six feet by two, with a straw-filled mattress if he was lucky and bare boards if he wasn’t. He would have been told to bring his own provisions for the voyage, or to buy them from the ship’s stores at inflated prices. Oatmeal, hardtack, dried peas, maybe some salt pork. Water from casks that grew foul within a week. A tin cup and a wooden bowl.

The crossing took four to eight weeks, depending on the wind, the weather, and whether the ship was stopped, searched, or diverted. Westbound crossings were slower as the prevailing winds blew east, and winter crossings were brutal. The steerage deck was dark, the air heavy with the smell of unwashed bodies, vomit, and bilge water. Seasickness was universal and unrelenting for the first days. The food was monotonous and often barely edible. There was no privacy, no quiet, no escape from the constant rolling of the ship and the groaning of the timbers and the retching of the people around you.

But the ship moved west. Day by day, it moved west.

New York Harbor. After a month or two at sea, the flat line of Long Island appeared to the north, then the Narrows, then the wide mouth of the harbor itself, and suddenly the city — small by the standards Philip’s grandchildren would know, but startling after weeks of empty ocean. Church steeples and ship masts. Wharves running along the East River, crowded with vessels of every size. The noise carrying across the water — hammers, shouts, the creak of cargo cranes, the screaming of gulls.

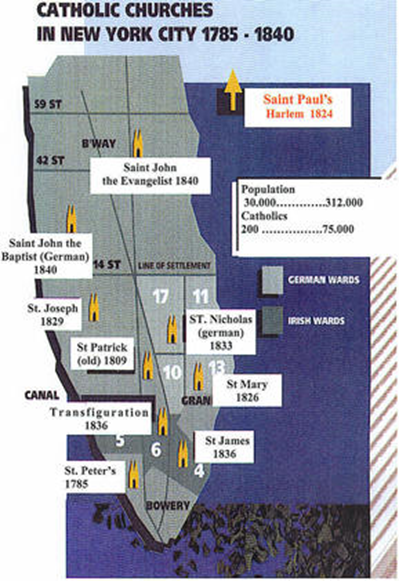

There was no Ellis Island. No Castle Garden. No immigration station of any kind. Those institutions wouldn’t exist for decades. In 1811 or 1812, an arriving emigrant simply walked off the ship onto the wharf and into the city. No one checked your papers. No one asked your name. No one cared, particularly, whether you lived or died, as long as you didn’t become a public charge.

Philip stepped onto the wharves of lower Manhattan with his tools, his clothes, and whatever money he had left after the passage. He was a blacksmith in a fast-growing city that needed blacksmiths. That was his advantage, and it was considerable. New York in 1811 was a city of roughly 100,000 people, expanding in every direction, building constantly. The waterfront hummed with shipbuilding and repair. The streets were full of horses that needed shoeing, carts that needed mending, and buildings that needed iron hardware. A skilled smith who was willing to work could find employment within days.

Philip found it. We don’t know the details — whether he worked for another smith at first, or rented forge space, or found a patron who set him up. But by the time the city directory was compiled in late 1813, Philip Heenan was listed at 7 Hague Street, a smith with his own address. Hague Street sat in the tangle of lanes just north of the waterfront, in the Fourth Ward, the kind of neighborhood where tradesmen and artisans clustered because the rents were affordable and the customers were close. The docks were a few blocks south. The construction trades were everywhere. It was exactly where a blacksmith would plant himself.

Hague Street is gone now. The Brooklyn Bridge buried it in the 1870s, its massive stone anchorage planted directly on the ground where Philip’s forge once stood. But in 1813, it was a working street in a working neighborhood, and Philip was on it, established, listed, real.

He may have been ready for Sarah and the children as early as 1812, but the war had closed off that option, and all they could do was wait and hope. Letters home were certainly attempted. But given wartime logistics, it’s doubtful how many were able to be exchanged. Costs were high. The War sharply reduced transatlantic sailings. Reliability was poor. Ships were captured, delayed in port by embargoes, or avoided sailing altogether. Transit times varied widely. In peacetime, letters typically took 4–8 weeks. During 1812–1814, delivery commonly took 2–4 months and could be much longer, with many letters simply lost.

Philip was settled. He had a forge. He had an address. It was time for the family to come, but there was no way they could make the trip. Sarah would have known of the problems. She would have known of the war. The docks at Dublin were full of stories about ships taken, cargoes confiscated, crews imprisoned. The war dragged on through 1812, 1813, 1814. It must have been agonizing.

News of the Treaty of Ghent reached New York in February 1815. By spring, the Atlantic was opening again — not safe, exactly, but no longer an active battlefield.

It is possible that Sarah’s mother, Jane Dempsey, traveled with her. Jane was living at the Heenan household address in New York at the time of her death in 1828. She may have crossed the Atlantic with her daughter and grandchildren, an older woman providing the practical help and the social standing that a lone mother with small children would have needed on a voyage of several weeks. Two women and three children were a family. One woman and three children was a vulnerability. Whether Jane came with Sarah or followed later, we don’t know. But her presence in the household suggests she was part of the story, not an afterthought.

The journey Sarah faced was the same journey Philip had made, and worse. The same steerage berths, the same foul air, the same weeks of rolling darkness. But now add the children who were frightened and seasick and bored and hungry and unable to understand why they were living in the belly of a ship. Add the constant vigilance — making sure no one fell, no one wandered, no one ate something that would make them sick, no one caught the fevers that swept through steerage decks. Add the loneliness of being the only person responsible for keeping everyone alive.

Sarah did it — with Jane’s help or without, before the war ended or after. She got them across. She brought them to New York, to Philip, to Hague Street, to whatever rooms he’d arranged in whatever building he’d found near the forge.

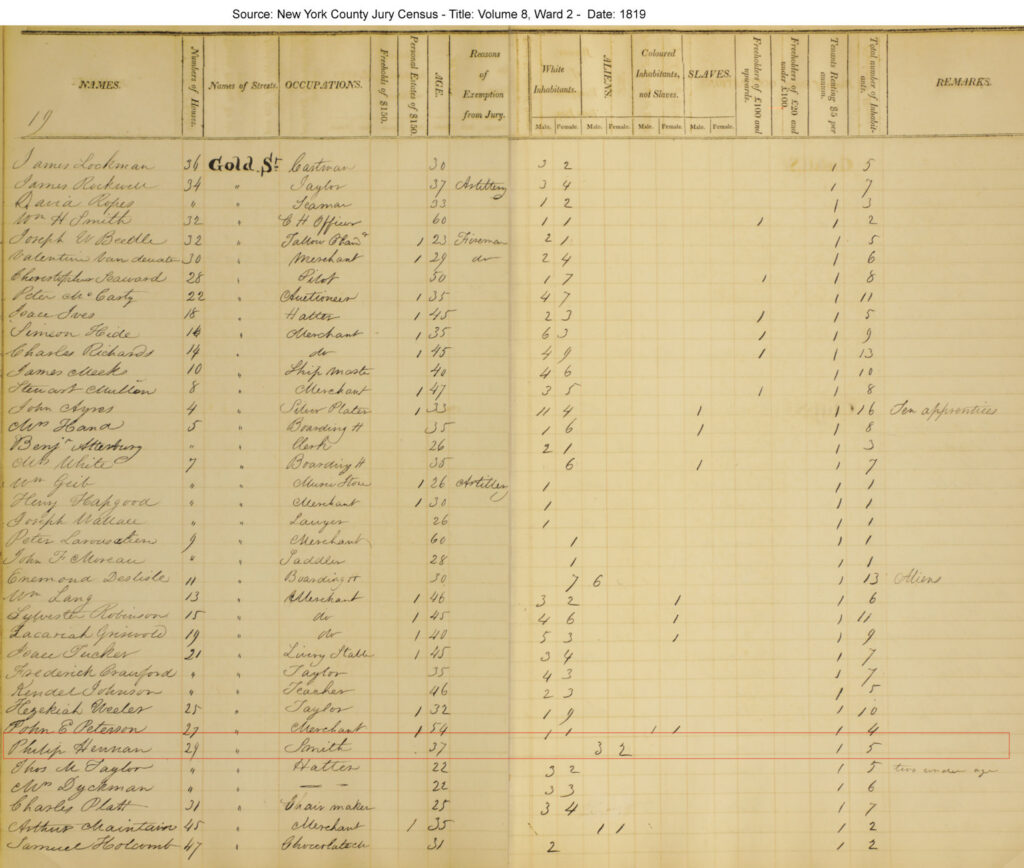

They stayed at 7 Hague Street for three years until moving to Gold Street where the 1819 City Jury Census finds them at number 29. Five persons. Three males, two females. All aliens. Almost certainly Philip, Sarah, Ellen, John Michael, and William. The family, together. Settled. Five people in a city of immigrants, in a neighborhood of tradesmen, in rooms that were probably no bigger or grander than the ones they’d left behind in Dublin.

But the ceiling was gone. The invisible ceiling that had pressed down on Philip in Dublin, the Penal Laws, the guild system that shut Catholics out, the contracts he couldn’t get, the property he couldn’t own, the civic life he couldn’t join, none of that applied here. In New York, a Catholic blacksmith could work for whoever would pay him. He could own property. He could become a citizen. He could build a future his children might actually inherit.

However they made the journey — together or in stages, before the war or during it, through Liverpool or direct from Dublin — the Heenans had bet everything on New York. Philip had walked away from the only city he’d ever known, crossed an ocean in wartime, and built a life from nothing in a strange country. Sarah had followed him into the unknown, with children clinging to her, trusting that the man she’d married had made the right decision. They had risked it all.

And by 1819, New York City’s juror census confirms to us that they were all together. Five Irish immigrants in lower Manhattan, with a forge and a trade and a future that Dublin would never have given them. But it was a future in which fate’s twists would prove cruel.